A rather popular tale concerns the isolated population that lived on Easter Island. They were alone, very alone. The nearest inhabited island to them is 1,289 miles away, so as far as they were concerned, the entire universe was just them. I confess that I’ve always had an interest ever since reading Aku-Aku; The 1958 Expedition to Easter Island by Thor Heyerdahl when I was a teen. (Yea, I was weird, I read stuff like that at that age).

What changed everything was the arrival of Europeans in 1722. Suddenly a whole new world opened up for them.

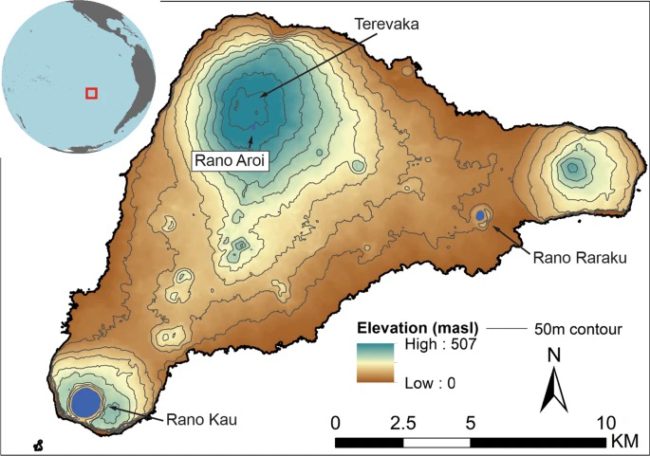

You will perhaps know Easter Island as the home of nearly 1,000 statues called moai that are scattered over this tiny island. (See picture above for an example of several). The island is about 15.3 miles long and is 7.6 miles at its widest point, so that really is rather a lot of moai to pack into a tiny island.

The Tale of caution for our Age

The story is briefly this.

Their culture thrived, blossomed, and supported tens of thousands of people. Sadly, because of their fanatical beliefs, over time they ended up chopping down all their trees. This is because they were using them to move the maoi into position on wooden rollers. The outcome is that they ended up destroying their biodiversity and their ability to live on the island. When the ecosystem collapsed, their population then rapidly shrank and dwindled. By the time the Europeans arrived in 1772 they were mostly all gone.

Why this just a myth ?

No, it was once the prevailing scientific hypothesis. You can find it explained as “fact” here within a Smithsonian article written as recently as 2007 …

On this outpost nearly 2,300 miles west of South America and 1,100 miles from the nearest island, the newcomers chiseled away at volcanic stone, carving moai, monolithic statues built to honor their ancestors. They moved the mammoth blocks of stone—on average 13 feet tall and 14 tons—to different ceremonial structures around the island, a feat that required several days and many men.

Eventually the giant palms that the Rapanui depended on dwindled. Many trees had been cut down to make room for agriculture; others had been burned for fire and used to transport statues across the island. The treeless terrain eroded nutrient-rich soil, and, with little wood to use for daily activities, the people turned to grass. “You have to be pretty desperate to take to burning grass,” says John Flenley, who with Paul Bahn co-authored The Enigmas of Easter Island. By the time Dutch explorers—the first Europeans to reach the remote island—arrived on Easter day in 1722, the land was nearly barren.

It is a story that is viewed as a metaphor of life on our planet. This morality tale plucked from an actual observation of what happened is also presented as a warning to all of us. We need to take care of the limited resources we have. If we don’t, then we face the same fate on a global scale.

Oops

There is however one small flaw with all of this. A new study that has just been published reveals that our morality tale is a myth. It did not happen that way at all.

Nature Communications: Approximate Bayesian Computation of radiocarbon and paleoenvironmental record shows population resilience on Rapa Nui (Easter Island)

This new research has been conduced by Binghamton University anthropologists Robert DiNapoli and Carl Lipo. It was published (open access) at the above link on June 24, 2021.

What they reveal is that the island experienced steady population growth from its initial settlement until European contact in 1722. It never had more than a few thousand people prior to European contact, and their numbers were increasing rather than dwindling.

What did the Researchers do to determine this new insight?

The popular tale was actually an insight that dated to roughly about the 1960s. Various uncertainties have always existed for that, so this paper is not a huge surprise to those familiar it all, it simply raises the confidence that the previous understanding from the 1960s is indeed wrong.

The press release from the University explains it as follows …

Archaeologists have different ways to reconstruct population sizes using proxy measures, such as looking at the different ages of individuals at burial sites or counting ancient house sites. That latter measure can be problematic because it makes assumptions as to the number of people who live in each house, and whether the houses were occupied at the same time, DiNapoli said.

The most common technique, however, uses radiocarbon dating to track the extent of human activity during a moment in time, and extrapolating population changes from that data. But radiocarbon dates can be uncertain, DiNapoli acknowledged.

For the first time, DiNapoli and Lipo have presented a method that is able to both resolve these uncertainties and show how changes in population sizes relate to environmental variables over time.

Standard statistical methods don’t work when it comes to linking the radiocarbon data to environmental and climate changes, and the population shifts connected with them. To do so would involve estimating a “likelihood function,” which is currently difficult to compute. Approximate Bayesian Computation, however, is a form of statistical modeling that doesn’t require a likelihood function, and thus gives researchers a workaround, DiNapoli explained.

Using this technique, the researchers determined that the island experienced steady population growth from its initial settlement until European contact in 1722. After that date, two models show a possible population plateau, while another two models show possible decline.

In other words the popular morality take of the collapse of their civilisation because they chopped down all the trees is not actually true at all and is simply a modern myth.

It turns out that the few thousand who lived on the island adapted and successfully thrived over many generations. The real story here is that they are in fact an example of resiliency and sustainability.

Does this mean that this is really a climate change denial story?

Nope.

It is however inevitable that some are a tad pissed about having their favourite ecological morality tale debunked.

The researches, when faced with the “climate-change denial” charge, defended themselves like this …

Lipo acknowledged that proponents of the Easter Island collapse story tend to see him as a climate-change denier; that’s emphatically not the case. But he cautioned that the ways ancient peoples dealt with climate and environmental changes aren’t necessarily reflective of current global crises and their impact in the modern world. In fact, they may have a good deal to teach us about resilience and sustainability.

“There’s a natural tendency to think that people in the past aren’t as smart as we are and that they somehow made all these mistakes, but it’s really the opposite,” Lipo said. “They produced offspring, and the success that created the present. Even though their technologies might be more simple than ours, there is so much to be learned about the context in which they were able to survive.”

The real lesson here is still a tale for us to pay attention to.

Around the year 1500, there was a climactic shift in the Southern Oscillation index; that shift led to a dryer climate on Rapa Nui. When their climate altered to a dryer climate, they adapted by modifying their behaviour and so they demonstrated resilience and sustainability.

So here is how things actually played out …

… there is no evidence that the islanders used the now-vanished palm trees for food, a key point of many collapse myths. Current research shows that deforestation was prolonged and didn’t result in catastrophic erosion; the trees were ultimately replaced by gardens mulched with stone that increased agricultural productivity. During times of drought, the people may have relied on freshwater coastal seeps.

Construction of the moai statues, considered by some to be a contributing factor of collapse, actually continued even after European arrival.

In short, the island never had more than a few thousand people prior to European contact, and their numbers were increasing rather than dwindling, their research shows.

“Those resilience strategies were very successful, despite the fact that the climate got drier,” Lipo said. “They are a really good case for resiliency and sustainability.”

We also face drastic climate change. In our case, it is not natural but instead is the result of our current behaviour – burning fossil fuels. Our choice is that we either adapt or we don’t. If we don’t, but instead simply carry on doing the same, then our future will indeed be bleak. We face choices. We can still take meaningful decisive actions and switch away from belching out vast amounts of CO2 or not.

Whatever version of this tale you embrace, there is no avoiding the fact that it is indeed acting as a metaphor for the bigger picture. They adapted, modified their behaviour and so they survived and flourished when their climate became naturally dryer. Should we not also be inspired by their example and modify our behaviour as well?

The moment of choice for us is now.

Further Reading

- Press Release – Resilience, not collapse: What the Easter Island myth gets wrong

- Study (Open Access) Nature Communications – Approximate Bayesian Computation of radiocarbon and paleoenvironmental record shows population resilience on Rapa Nui (Easter Island)