No, Christopher Hitchens has not had a sudden conversion, but he has indeed written an article within the May edition of vanity Fair in full support of the Bible. He argues that our language and culture are incomplete without this 400-year-old book—the King James translation of the Bible. It was spurned by the Establishment, so it really represents a triumph for rebellion and dissent.

No, Christopher Hitchens has not had a sudden conversion, but he has indeed written an article within the May edition of vanity Fair in full support of the Bible. He argues that our language and culture are incomplete without this 400-year-old book—the King James translation of the Bible. It was spurned by the Establishment, so it really represents a triumph for rebellion and dissent.

Here are a couple of extracts …

… For the first 1,500 years of the Christian epoch, this problem of “authority,” in both senses of that term, was solved by having the divine mandate wrapped up in languages that the majority of the congregation could not understand, and by having it presented to them by a special caste or class who alone possessed the mystery of celestial decoding.

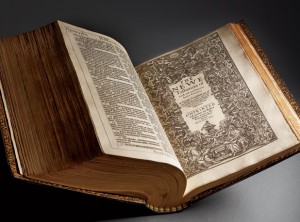

Four hundred years ago … an extraordinary committee of clergymen and scholars completed the task of rendering the Old and New Testaments into English

Hitchens then proceeds to outline the historical context for this, explains what was going on at the time, who the translators were and what drove them …

..Until the early middle years of the 16th century, when King Henry VIII began to quarrel with Rome about the dialectics of divorce and decapitation, a short and swift route to torture and death was the attempt to print the Bible in English. It’s a long and stirring story, and its crux is the head-to-head battle between Sir Thomas More and William Tyndale.

…

Tyndale whenever possible was loyal to the Protestant spirit by correctly translating the word ecclesia to mean “the congregation” as an autonomous body, rather than “the church” as a sacrosanct institution above human law. In English churches, state-selected priests would merely incant the liturgy. Upon hearing the words “Hoc” and “corpus” (in the “For this is my body” passage), newly literate and impatient artisans in the pews would mockingly whisper, “Hocus-pocus,” finding a tough slang term for the religious obfuscation at which they were beginning to chafe.

…

Though I am sometimes reluctant to admit it, there really is something “timeless” in the Tyndale/King James synthesis. For generations, it provided a common stock of references and allusions, rivaled only by Shakespeare in this respect. It resounded in the minds and memories of literate people, as well as of those who acquired it only by listening. From the stricken beach of Dunkirk in 1940, faced with a devil’s choice between annihilation and surrender, a British officer sent a cable back home. It contained the three words “but if not … ” All of those who received it were at once aware of what it signified. In the Book of Daniel, the Babylonian tyrant Nebuchadnezzar tells the three Jewish heretics Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego that if they refuse to bow to his sacred idol they will be flung into a “burning fiery furnace.” They made him an answer:“If it be so, our god whom we serve is able to deliver us from the burning fiery furnace, and he will deliver us out of thy hand, o King. / But if not, be it known unto thee, o king, that we will not serve thy gods, nor worship the golden image which thou hast set up.”

All this, and much more, can be read here in full (Its Hitchens at his best, you will not be disappointed)

Do not hold any illusions, this is not in any way an endorsement for the words of a supernatural entity, it is instead in praise of a piece of literature penned from the minds of men. There is no escaping the immense impact it has had upon our culture, and so while we might discard the irrational superstitions, we can still admire the beauty of the written word.

As for the players themselves, yes Tyndale was a man of his age and truly believed, but what he did was in itself a huge leap forward that broke the power welded by the ecclesiastical authorities. No longer could they dictate what individuals should think and believe, instead individuals could read it all for themselves, think, and make up their own minds. Now that is something I find to be profoundly democratic.

whatsoever things are true, whatsoever things are honest, whatsoever things are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely, whatsoever things are of good report; if there be any virtue, and if there be any praise, think on these things.