If you are wondering what TIL within the title means, well that is an abbreviation for “Today I Learned”.

If you are wondering what TIL within the title means, well that is an abbreviation for “Today I Learned”.

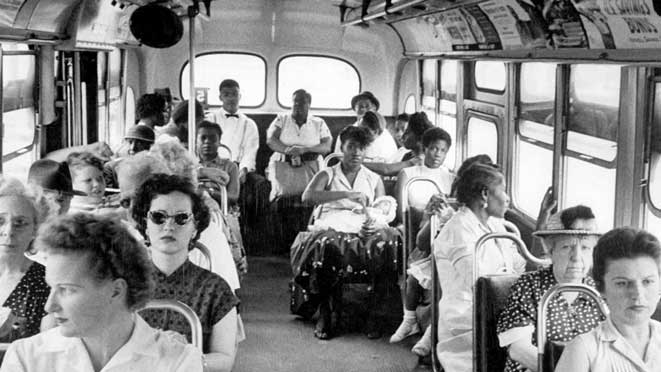

Let me throw a scenario out to you. Cast your mind back to bus journey in 1955 Montgomery, Alabama where the way things worked then was as follows; As white people boarded, they took their seats in the front rows and filled the bus towards the back. Black people who boarded the bus filled the back rows working towards the front. Eventually they met and so the bus would be full. Once that happened this is how it then worked. Another black person entering would be expected to stand, but if a white person got on, then everybody in the black row nearest the front would have to stand so that it could then become a white row for the white person to sit. 1955 is famous because in this scenario there was a young black girl who refused to stand, was arrested and so stepped into history.

Who am I referring to?

The name that immediately springs to mind is of course Rosa Parks, however, what I did not appreciate was that she was not the first. Nine months before the Rosa Parks incident, 15 years old Claudette Colvin took the exact same stance, and yet history remembers Rosa Parks and not Claudette Colvin, so what happened and why is not only interesting, but should also be remembered and not forgotten.

The Incident

Claudette Colvin was a feisty passionate 15 year old who was quite different than the mild mannered Rosa Parks, and so here is what happened …

It was this dark, clever, angry young woman who boarded the Highland Avenue bus on Friday, March 2, 1955, opposite Martin Luther King’s church on Dexter Avenue, Montgomery. Colvin took her seat near the emergency door next to one black girl; two others sat across the aisle from her. The law at the time designated seats for black passengers at the back and for whites at the front, but left the middle as a murky no man’s land. Black people were allowed to occupy those seats so long as white people didn’t need them. If one white person wanted to sit down there, then all the black people on that row were supposed to get up and either stand or move further to the back.

As more white passengers got on, the driver asked black people to give up their seats. The three other girls got up; Colvin stayed put. “If it had been for an old lady, I would have got up, but it wasn’t. I was sitting on the last seat that they said you could sit in. I didn’t get up, because I didn’t feel like I was breaking the law.”

To complicate matters, a pregnant black woman, Mrs Hamilton, got on and sat next to Colvin. The driver caught a glimpse of them through his mirror. “He asked us both to get up. [Mrs Hamilton] said she was not going to get up and that she had paid her fare and that she didn’t feel like standing,” recalls Colvin. “So I told him I was not going to get up, either. So he said, ‘If you are not going to get up, I will get a policeman.'”

The atmosphere on the bus became very tense. “We just sat there and waited for it all to happen,” says Gloria Hardin, who was on the bus, too. “We didn’t know what was going to happen, but we knew something would happen.”

Almost 50 years on, Colvin still talks about the incident with a mixture of shock and indignation – as though she still cannot believe that this could have happened to her. She says she expected some abuse from the driver, but nothing more. “I thought he would stop and shout and then drive on. That’s what they usually did.”

But while the driver went to get a policeman, it was the white students who started to make noise. “You got to get up,” they shouted. “She ain’t got to do nothing but stay black and die,” retorted a black passenger.

The policeman arrived, displaying two of the characteristics for which white Southern men had become renowned: gentility and racism. He could not bring himself to chide Mrs Hamilton in her condition, but he could not allow her to stay where she was and flout the law as he understood it, either. So he turned on the black men sitting behind her. “If any of you are not gentlemen enough to give a lady a seat, you should be put in jail yourself,” he said.

A sanitation worker, Mr Harris, got up, gave her his seat and got off the bus. That left Colvin. “Aren’t you going to get up?” asked the policeman.

“No,” said Colvin.

He asked again.

“No, sir,” she said.

“Oh God,” wailed one black woman at the back. One white woman defended Colvin to the police; another said that, if she got away with this, “they will take over”.

“I will take you off,” said the policeman, then he kicked her. Two more kicks soon followed.

For all her bravado, Colvin was shocked by the extremity of what happened next. “It took on the form of harassment. I was very hurt, because I didn’t know that white people would act like that and I … I was crying,” she says. The policeman grabbed her and took her to a patrolman’s car in which his colleagues were waiting. “What’s going on with these niggers?” asked one. Another cracked a joke about her bra size.

“I was really afraid, because you just didn’t know what white people might do at that time,” says Colvin. In August that year, a 14-year-old boy called Emmet Till had said, “Bye, baby”, to a woman at a store in nearby Mississippi, and was fished out of the nearby Tallahatchie river a few days later, dead with a bullet in his skull, his eye gouged out and one side of his forehead crushed. “I didn’t know if they were crazy, if they were going to take me to a Klan meeting. I started protecting my crotch. I was afraid they might rape me.”

They took her to City Hall, where she was charged with misconduct, resisting arrest and violating the city segregation laws. The full enormity of what she had done was only just beginning to dawn on her. “I went bipolar. I knew what was happening, but I just kept trying to shut it out.”

She concentrated her mind on things she had been learning at school. “I recited Edgar Allan Poe, Annabel Lee, the characters in Midsummer Night’s Dream, the Lord’s Prayer and the 23rd Psalm.” Anything to detach herself from the horror of reality. Her pastor was called and came to pick her up. By the time she got home, her parents already knew. Everybody knew.

“The news travelled fast,” wrote Robinson. “In a few hours, every Negro youngster on the streets discussed Colvin’s arrest. Telephones rang. Clubs called special meetings and discussed the event with some degree of alarm. Mothers expressed concern about permitting their children on the buses. Men instructed their wives to walk or to share rides in neighbour’s autos.”

It was going to be a long night on Dixie Drive. “Nobody slept at home because we thought there would be some retaliation,” says Colvin. An ad hoc committee headed by the most prominent local black activist, ED Nixon, was set up to discuss the possibility of making Colvin’s arrest a test case. They sent a delegation to see the commissioner, and after a few meetings they appeared to have reached an understanding that the harassment would stop and that Colvin would be allowed to clear her name.

When the trial was held, Colvin pleaded innocent but was found guilty and released on indefinite probation in her parents’ care. “She had remained calm all during the days of her waiting period and during the trial,” wrote Robinson. “But when she was found guilty, her agonised sobs penetrated the atmosphere of the courthouse.”

Nonetheless, the shock waves of her defiance had reverberated throughout Montgomery and beyond.

Why Rosa Park, and why have we forgotten this?

Colvin was 15, feisty, very very poor, and also pregnant. The community desperately needed a publicly acceptable hero and so they decided to wait. Claudette herself observes …

“My mother told me to be quiet about what I did. She told me to let Rosa be the one: white people aren’t going to bother Rosa, they like her”

Parks was an ideal candidate to go through a court challenge and confront the gross injustice, so she stepped forward and has her official place in history. However, rather ironically, the Parks case became bogged down in the courts, and it was another case, the Browder v. Gayle case, that finally succeeded in 1956.

What was that Browder v. Gayle case that actually won the victory?

Civil rights activists reconsidered Claudette Colvin. Fred Gray, a civil rights activist was concerned that the Parks case would (as it did) become bogged down in state courts, and so he took a new case directly to the Federal courts on behalf of Colvin and several others who had been discriminated against by bus drivers. He won, and it was legally established on June 5, 1956 that bus segregation was unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment.

So was it actually Claudette Colvin who first dared to defy the absurd segregation?

Actually no, others had also refused to comply. There was Bayard Rustin in 1942, Irene Morgan in 1946, Sarah Louise Keys in 1952, it was however Colvin’s legal case that won, and yet history remembers Rosa Parks because her specific act of disobedience served as a potent and powerful symbol of defiance, so she became a symbol of a revolution that inspired many passive souls into taking decisive action.

Incidentally, Claudette Colvin is still alive today and lives in a retirement home in New York.

“Young people think Rosa Parks just sat down on a bus and ended segregation, but that wasn’t the case at all.” – Claudette Colvin