Now you might be wondering what this means, so lets focus down on that with a specific example

- workers work harder to maintain ownership of a provisional awarded bonus than they did for a bonus framed as a potential yet-to-be-awarded gain (This specific example is discussed in “Carrots dressed as sticks”. (2010). Economist, 394(8665), 72.).

Let’s consider another example from a real study. Suppose there exists a mug, so what is it worth?

- If you do not own a mug then to get one, you have to exchange some money or goods to get it – we can refer to the quantity you would be prepared to pay as the willing to pay (WTP) amount

- If however you do own the mug, it is yours, then we can refer to the quantity you would be prepared to accept in exchange for it as the willing to accept (WTA) amount

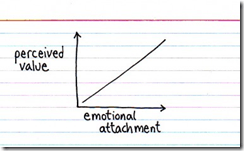

Now this is where it gets interesting, there is a discrepancy between the WTP and WTA quantities and that difference is down to your personal ownership of the item itself – the more attached you are the greater the discrepancy.

You can find a study that utilised mugs to demonstrate this – Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (2009). Experimental Tests of the Endowment Effect and the Coase Theorem. In E. L. Khalil (Ed.)

OK, so what?

Well, what is rather obviously at the root of all this is that once you own something and have an emotional attachment to it, your willingness to part with it will cause loss aversion to kick in, and so your WTA will be higher that the other person’s WTP. That is a rather glaring contradiction to standard economic theory which asserts that a person’s willingness to pay (WTP) for a good should be equal to their willingness to accept(WTA) compensation to be deprived of the good, a hypothesis which underlies consumer theory and indifference curves.

Yes but how does this actually play out?

Well if you need somebody to do something, then giving them ownership of the decision will greatly motivate them to act. If for example you ask “Can you do X”, you may find resistance. However, if you instead present a problem, and let them then suggest how they can assist by providing a solution X, then it was not you asking them to do X, but rather is was their idea to perform X to help you, so they now own the idea and so the willingness to act is there.

Rewards and Points

Here is another variation, and this is where it gets even more interesting … give somebody a coffee card with 9 slots for stamps, then tell them that if they fill the card the 10th is free. Ah but if you give then a card with 15 slots, and the first 5 have already been pre-stamped, what happens? Interestingly enough, ownership of the pre-stamped cards appears to greatly motivate those pre-stamped cards to be filled much more so than empty cards … but wait, it is still 9 stamps to get 1 free coffee, so nothing has actually changed except ownership.

Hide the Obstacles until the end

The deeper into the task you are, the greater the degree of ownership and attachment you have to it and that can influence how you respond to obstacles – the classic example that illustrates this is the rat in a maze. Place a reward at the end (cheese), then set the rat running with a harness that will stop the rat and also measure how strongly the rat pulls against the harness to keep going and get the reward. An early stop and the rat will pull moderately, but a late stop, one in which the cheese is just around the corner and almost in reach, will result in a rat that will pull vigorously against the harness.

Make them feel special

Making people feel truly privileged also motivates as well and enables them to grasp some specific ownership. Researchers looking into reward programs made a rather interesting discovery. For example giving customers a card to be stamped … collect 9 and 10th is free … was not as successful as suggesting that they had been especially selected to be part of the program because of their purchase history, and so it was no longer a random card, it was now their card, they owned it, and they had been especially chosen (along with every other customer). So while the actual selection criteria was they they were simply breathing and had walked in the door, they were made to feel special and by doing so took some ownership, and that then motivated them to keep coming.

Pulling the strings

Now think about all those nudges you get, all those reward cards and loyalty programs with bronze and then silver and gold levels. We might indeed understand and grasp that we are being given some emotional motivation to come back because we now own a bit more and have been made to feel special – we do know this, and yet we accept it anyway because we do want to complete the set and get that 10th free one that we already have some ownership of.

Games … get the free game, invest a bit of time and oh … time to now buy the key to open up the next bit, and after having already invested the time, we happily do so.

Perhaps the most successful player of this is religion. The beliefs that thrive today, thrive because they are naturally good at enabling us to feel especially chosen and part of a special relationship. We keep coming back for more rewards each week, the welcome, the community, the time invested, and so it is not simply an idea, but rather is a deep emotional attachment.

If you debate people who deeply embrace religious ideas, you might wonder why, after you robustly debunk the ideas, nothing happens and then happily continue. Well that is perhaps because the ideas and beliefs are almost an after thought, they already have their personal reward card stamped each and every week, they own it and have no desire to give it all up, their WTA the things that are really true price is not on par with the WTP debunking of the core ideas due to the deep emotional investment that exists.

… and yet sometimes people really do escape and find something far better.