The what?

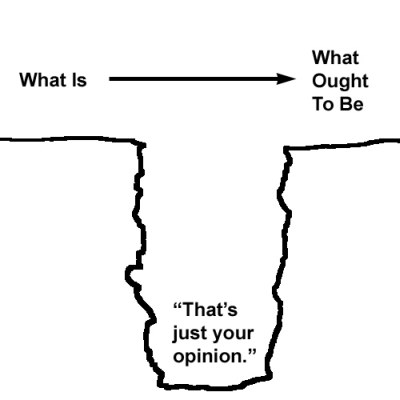

OK, so let me explain. The essence if it is this:, you can’t really make a claim about what ought to be on the basis of what is. The observation is that many make a jump from descriptions of what is to how we should behave. That is essentially a leap over a vast and often unbridgeable chasm.

What am I babbling about?

There are facts we know, facts that describe things. The word used to encapsulate that concept is “descriptive”. We also have people making statements about how we should behave and often they use descriptive facts as the basis for these “prescriptive” assertions.

For example:

Sex is for reproduction, therefore …

… people shouldn’t be having sex outside of marriage

… shouldn’t be having homosexual sex

… should only use sex to make a baby

etc…

That first statement is a descriptive statement of fact. The evolution of sex is indeed all about reproduction, but for the record this is also an incomplete statement, I’ll skip over that for now. Notice however that what then follows are directives that use this description of what is to try and justify a series of statements regarding how you ought to behave. If you happen to be religious then you might indeed accept this without giving it any thought because it is part of a religious cultural inheritance. If instead you pause for a moment, then you will appreciate that there is no logic connecting this description of what is to the statements that dictate how you ought to behave.

That is basically the is-ought problem.

This is specifically about morality, is-ought does actually work sometimes

Let’s be specific, about the scope here, we are thinking about moral directives that make a leap with no reason that justify doing so at all. Beyond moral directives is-ought can actually work …

- Description: Arsenic is deadly.

- Prescription: You ought not to drink Arsenic.

The first is a fact, and the second is not a moral directive as such, but instead is telling you implicitly that if you do drink it then there is a clear consequence (you die), hence not drinking it is a very practical means for avoiding such an undesirable outcome.

Origins

The disconnect between “is” statements and “ought” statements in the context of systems of morality comes from the well-known Scottish philosopher and historian David Hume. He has a rather famous book entitled A Treatise of Human Nature (1739), which he rather amazingly published when he was only 28. As a side note, at the time it was published, it was really not popular at all and almost ruined his university career. It was only later recognised as one of the most important works in the history of Western philosophy.

In every system of morality, which I have hitherto met with, I have always remarked, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning, and establishes the being of a God, or makes observations concerning human affairs; when of a sudden I am surprised to find, that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not. This change is imperceptible; but is, however, of the last consequence. For as this ought, or ought not, expresses some new relation or affirmation, ’tis necessary that it should be observed and explained; and at the same time that a reason should be given, for what seems altogether inconceivable, how this new relation can be a deduction from others, which are entirely different from it. But as authors do not commonly use this precaution, I shall presume to recommend it to the readers; and am persuaded, that this small attention would subvert all the vulgar systems of morality, and let us see, that the distinction of vice and virtue is not founded merely on the relations of objects, nor is perceived by reason

In other words, what is is telling us is that in the context of morality people deploy “ought” statements that simply cannot be derived from previous given “is” statements.

So how then do you work out what is and is not Moral?

Is it possible to bridge this is-ought gap?

A solution is to not actually do that at all. You can instead think about goals and well-being.

Sam Harris does it as follows …

“If morality has to deal with not causing the suffering of conscious creatures, and if you want to live a moral life, you should take actions that don’t cause the suffering of conscious creatures.”

Now that is perhaps a better place to start from instead of trying to make an unjustifiable leap from facts to prescriptive demands that have no real justifiable basis.

(Continuation):

Description: Arsenic is deadly.

Prescription: You ought not to drink Arsenic.

This reasoning lacks a third statement in order to right: For example, “Dying is bad” or “Dying is something you ought to avoid”.

Those two are examples of normative, not descriptive, statements. It is about what it ought to be/be done. Without it, the prescription is just a logically random conclusion. So, what you ought to do here is inferred by two sentences: a descriptive and a normative one that the author does not mention. The normative one is definitely not inferred from a descriptive sentence; or, if it is, it needs to be inferred also from another normative statement and not just a descriptive one. So, this example fails to show how the is-ought gap has exceptions. In any case, one could think: “if Arsenic is deadly and I want to die, I ought to drink Arsenic”, thus challenging the connection between the description and the prescription in the example.

The point Hume made here was that for any normative statement, you need another normative statement to justify it, and this goes to infinity. As a consequence, it is impossible to ever justify any normative claim. Even those normative statements Harris made about morality, need further normative justification that will never be over, according to Hume. Hume solves this by treating moral judgments not as statements in the same sense descriptive statements are statements, but as the expression of emotions. Like if saying: “raping a woman is bad” were the same as “boooo! to raping a woman”.

It is also a mistake to say that the is-ought problem is only about ethics. It is about all normative claims, including epistemic and logic ones (those about how we ought to reason).

This article is from 2017, but since it is still here i have to make a comment about the author’s claim that the is-ought gap. It is not a fallacy to derivate an ought from an is, particularily if we pay attention to ethical naturalism. The is-ought is a philosophical problem and not a fallacy. It is a fallacy when that connection is not explicit. Hume thought it was impossible to link the is to the ought, but there are some authors that think it is possible. That is why a more propper approach to this is to call it a “problem” and not a “fallacy”.

Secondly, it is false that the next example is a right inference and that it is an inference from an is to an ought: